The little girl was mean. She enjoyed being mean. She cussed. She picked fights. She bossed adults around. She was everything a girl is not supposed to be. Girls are supposed to be sugar and spice and everything nice, but this child? Zero grams sugar. Absolutely nothing nice. Spice factor? 100% cayenne pepper.

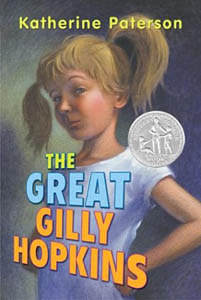

I’m talking about none other than The Great Gilly Hopkins, eponymous protagonist of Katherine Paterson’s 1978 novel. Gilly, or Galadriel, is the meanest foster kid around. Nobody messes with her because her sassy armor is impenetrable…that is, until she arrives in Thompson Park. When Gilly realizes the kind townsfolk are disintegrating her defenses, she hatches a plan that inadvertently sabotages her chance for happiness.

The film adaptation premiered in 2015, with a cast including Kathy Bates and Glenn Close.

For those who don’t know, Katherine Paterson writes award-winning, heartfelt books with the same ease required to open a can of tuna. Newberry’s, National Book Awards, and plenty of others gild her accolades. Paterson has been on my reading shelf ever since I was old enough to read a chapter book all by myself. Her ability to capture the sincerity of adolescence without any saccharine dazzled me then and now. I still marvel at her finesse rendering the real world and everyday life. I envy this skill the same way I greened at the math nerds at school who whipped through the quadratic equation.

But in Gilly, Paterson accomplishes something far greater and much more complex than verisimilitude. She crafts a sympathetic, compelling, and very likable female protagonist who is also mean; who misbehaves and shoves back; and who revels in her own wickedness.

I can’t count the times I have seen these characters get bashed around in critique groups. Trying to be helpful, writers advise the author to…keep the girl’s spunk, but go easy on her cruelty. Or…I’d like her more if she wasn’t so mean. Or…have you considered making your main character a boy?

Make her a boy? What — are girls not allowed to be mean or aggressive or spiteful?

Actually, they’re not. At least according to lots of reporting on social science research:

For Women Leaders, Likability and Success Hardly Go Hand-in-HandThe Social Science Behind “Bossiness”The Price Women Leaders Pay for Assertiveness–and How to Minimize ItWhat Does Social Science Say About How a Woman President Might Lead?

Time and again, the research shows that men are rewarded for being bossy, assertive, aggressive, etc. even to the point of being jerkbags. But women who exhibit similar behavior are relegated to the bitch-bin.

And at the risk of enraging just about every woman on the planet who spent $10 or more to see Wonder Woman — 2017 blockbuster film starring mostly women and directed by a woman — Diana, Princess of Themyscira, Daughter of Hippolyta, AKA Diana Prince, fully perpetuates the good girl stereotype.

Yes, she has amazing physical strength and can seriously kick some Axis Power butt. But she is also completely, entirely, holistically good. In every interview and behind-the-scenes profile I have seen, both Gal Gadot (who plays Diana) and director Patty Jenkins rave about the character’s quintessential goodness. This suggests the thematic intent to portray a good woman with mighty powers. But I take this a step further and attest that the only reason Diana can be so powerful is because she is also so good. The two traits are diametrically and proportionately linked. In other words, were she less like Captain America and more like Deadpool, moviegoers would not like her even half as much.

Contemporary society does not punish Diana for her powers. They do not relegate her to the Island of Ms-Fit Bossypantsuits because she is a good girl.

Which wraps back to Gilly, who is entirely likable despite spending most of the book being entirely rotten. A real brat. She blows bubble-gum bombs in adult’s faces. She savors violent fantasies. She bullies other children. She hate crimes her teacher. She steals. She lies.

So the real question is how in the hell (to quote Gilly) does Paterson achieve this? How does she trick our societal radar? And is her technique one that other writers can master for their own works?

I absolutely believe the technique is transferable! (Alas, the same cannot be said for the rest of Paterson’s prowess.) Essentially, give the bad protagonist (AKA anti-hero) a vulnerability. A weakness. A gap in the armor. Director Tim Miller puts this to brilliant use in the opening sequences of Deadpool.

First the camera pulls back from an assortment of crayons and a little tape deck blasting music. Our anti-hero perches on the railing of an interstate overpass. He is drawing his own stick-figure comic doodles (of himself lopping the head of his arch nemesis) while his ankles pendulum. To top it all off, Deadpool is singing along to the tunes — specifically Salt n’ Pepa’s 1993 hip-hop hit “Shoop.”

Following a brief monologue (the kind usually reserved for villains), Deadpool goes on to commit some pretty heinous atrocities. Over the course of the entire movie, he proves to be something like a leotard-clad Gilly Hopkins: foul-mouthed, sadistic, sarcastic, even a tad soul-less on his revenge quest. But it doesn’t matter to viewers. They’ve already seen him be just a bit vulnerable with those crayons and outdated pop music. They’ve already seen his soft spot and said: Awwww!

Paterson introduces Gilly with a similar hint of vulnerability. When readers meet Gilly, she sits in the back of the social worker’s car, chewing a wad of pink bubble-gum. As the social worker lectures her, Gilly blows a gigantic bubble, which pops and sticks to her hair. The novel could have just as easily opened with Gilly in the car turning her tooth brush into a shank knife — an action that fully shows and supports Gilly’s bad girl nature — however, such a start would not have exposed her weakness. Like that gum, Gilly turns out to be full of hot air. Like that gum, she softens. And just like Deadpool, Gilly goes on to commit some pretty unforgivable acts, but readers are already on her side.

And to get them there, she did not have to be good. Only vulnerable. Only a bit soft. Neither are the same as “good.” Instead, Paterson enabled a female character to be simultaneously “bad” and sympathetic. She enabled readers to encounter a true human being, and in doing so, she gave them a taste of true humanity.

So what say you, writers? Shall we get to work? Shall we labor with love on our anti-hero protagonists, making them authentically flawed, not artificially good flavored? Let’s a make a world where writers bring a Deadpool character to critique and leave with the feedback…have you considered making your bad protagonist a girl? Better still, let’s make a world where girls and boys, men, women, and everyone between or beyond those gender categories can simply be what they are and nonetheless loved.

Yorumlar