A pervasive color, temporal slip n’ slides, hop-scotching graphics, one voice to rule them all—everything you’ve ever loved in a Samuel Beckett play now in a graphic novel memoir!

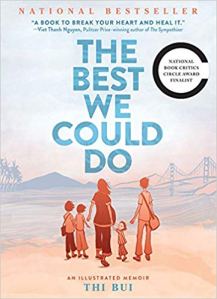

Bui, Thi. The Best We Could Do. New York: Abrams ComicArts, 2017. Print.

Genre: graphic novel memoir

Summary: A graduate school assignment turns into a decades-long quest to collect one family’s immigrant history morphs into a graphic memoir. The author recounts her family’s escape war-torn Vietnam and their rough, raw transition to America.

Critique: Orange hues pervade, warm, and stain every page and panel. It’s an apt color because the memoir roots back to Vietnam’s most turbulent and violent years of occupation, liberation, and civil insurrection. However, the unrelenting “Agent Orange” on every page adds as much as it detracts. To be sure it contributes an entire whispered universe of historic weight and suffering and survival. At the same time, it muddies the narrative timeline which alternates between then and now. The orange past is often indistinguishable from the orange present.

Perhaps this temporal slipperiness is exactly how the author lives with her heritage. The graphic novel may well be her attempt to share that experience with readers. And isn’t that one of the primary and most fundamental objectives embodied within every literary work? Creating that magical, telepathic exchange between the writer and the reader (to poorly paraphrase Stephen King from his memoir, On Writing). I believe it is, but I’m not convinced the exchange here has been entirely successful.

And the omnipresent orange is not the only culprit.

The confusion between past and present may also be tied to how this novel uses its panels. Commonly, graphic novel panels contain moments arranged sequentially—like individual frames from a movie reel. One panel can show a man approaching a door. The next can show keys sliding into a doorknob. The reader connects these two otherwise disconnected ideas: ah, that man is unlocking that door.

As Scott McCloud puts it in Understanding Comics, “…panels fracture both time and space, offering a jagged, staccato rhythm of unconnected moments.” Our minds have the power to fill in the gaps based on experience and prior knowledge, thereby creating a continuous narrative.

In this graphic novel, the moments within the panels are not entirely sequential. For instance, in one panel, you might have two people huddled at a dining room table. In the next panel, farmers work rice fields. It takes a while to decode that those farmers exist in the past and are being remembered by the people at the dining room table set in the present.

Presumably, the dialogue in that first panel would have made it clear that the subsequent panel was going to represent the memory being discussed. That’s not the case and is almost never the case because this novel rarely employs dialogue. Instead, exposition pervades the panels. It’s a one-way dialogue—the author’s monologue. Imagine watching a movie with no sound other than a voiceover telling you about what you’re seeing. Characters come together, interact, discuss, argue, but you don’t get to hear any of that. You only get the voiceover…for 330 pages.

Pervasive orange…. Temporal slip n’ slides…. Hop-scotching graphics…. One voice to rule them all.…

I can’t help feeling as if all these oddly juxtaposed elements should have combined into a brilliant, unconventional narrative. I mean, really, aren’t these precisely the kinds of bizarre components we know and love in every Samuel Beckett play?

Sigh. If only Samuel Beckett had made graphic novels.

Comments