Did you say dragons? In turn-of-the-last-century Vienna?? Enchanted and entrapped as everyday working Joes??? What ought to be a most marvelous storytelling feat turns into a lengthy, dozy tellingstory book.

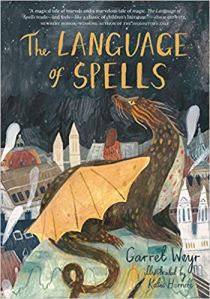

Weyr, Garret. The Language of Spells. Illus. Katie Harnett. Chronicle Books: San Francisco, 2018. Print.

Genre: middle grade fantasy

Summary: Grisha the dragon and his first best friend, Maggie — a young, human girl — set out to find and free the seventy or so dragons Sleeping-Beauty’ed and buried underground by a power-hungry sorcerer.

Critique: You know those old, possibly apocryphal, world maps which pointed to their own outer edges — those fringes marking the extent of human exploration — with dire Here Be Dragons! warnings? I feel obliged to put similar warnings around this book…

Here BeExposition!

For anyone unfamiliar with the literary component called exposition, I shall unbriefly elaborate. Exposition explains. It’s the information sections included in a book to summarize past events, ongoing actions, or a character’s thoughts and feelings and motivations.

When you’re not reading exposition, you’re most likely reading scenes, which are the moments when characters interact, talk, conflict, pick locks, unload groceries, kiss, dig tunnels, spy, gossip, or eat turnips.

Imagine you’re reading about Tillie, a supermarket cashier who’s beeping items over the scanner while the shopper unloading the cart prattles on about pineapples and their secret homeopathic applications. The point at which the text begins to explain how back in 1992, Tillie developed an extreme aversion to pineapples in the midst of a disastrous, tropical honeymoon getaway is the point at which you are reading exposition.

One minute, you were observing an interaction, gathering clues about the characters, making judgments and assumptions, forming opinions, and anticipating what’s to come. The next minute, you pause your work so that the author can inform you. Fill you in. Get you up to speed. Tell you a thing or two, rather than show you.

In good writing, exposition and scene go hand-in-hand. One is not better than other. Each involves the reader in a different way. Scenes make you work and spark your curiosity while exposition affirms your budding theories. In the best writing (which is also the best kind of storytelling), you never notice the narrative switching between the two tactics.

But in this book, you cannot help but notice that you are perpetually in exposition. Chapter after chapter, the author tells you this and tells you that. You are told that the dragons with golden eyes are put to work as tour guides in old museums and castles around Vienna. But what you want is to see this dynamic play out. You want to witness some of those interactions. You want to experience this strange, unfamiliar world where these chosen dragons must work or be eliminated; where these fire-breathing work-a-day Joes gather once a week at 2 a.m. at a hotel bar to share old war stories.

Heck, you want to hear those war stories, but instead, you are told about young Maggie sleeping under the nearby bar table where her poet father and his eccentric artist friends gab until dawn (amongst themselves and not with the dragons, by the way). You are told her entire backstory, about her mother’s tragic and untimely death, about her troubled interactions with other children, about her homeschooling, and her wanderings through the city on its new cable cars.

And bear in mind, much of what I have described here doesn’t arrive until you’re halfway through the book. The preceding chapters have been telling you about Grisha’s time enchanted and entrapped as a teapot.

Yes, you heard me right. You’ll spend nearly half a book watching a dragon teapot watch the world the change.

And so, dear readers, believe me when I tell you: He Be Exposition! Here be a book that opts for tellingstory instead of storytelling.

コメント