When the Sharks Gather: How Rituals Can Make Us Better Writers

Before I write, there’s this little thing that I do. Call it a ritual. I do it the same way every time. And according to neuroscience research, my little ritual is actually priming my brain to deliver a focused and confident writing session.

Here’s how it goes…

Everyday at 5:30 a.m., I zombie out of bed. I shuffle through the dark to the kitchen and switch on the electric teapot. I fill the pour-over with coffee and stack it atop my blue pot-bellied mug. As the water heats to life, I head to the living room to turn on the twinkle lights strung up since the holidays. Laptop boots. Notebooks and pens assemble. Coffee trickles into cup.

Lastly, I break off a nub of chocolate from the stash in my goody-drawer. I hold this nub lovingly and whisper to it a little prayer of sorts. Seems appropriate. Chocolate is, after all, theobroma, food of the gods. Muse munchums. To this heavenly food I give my thanks for its nourishment and my request to please nourish me now during my creative hijinx. I savor that nub of chocolate. Then I slide into my reclining wingback chair and set off on a two-hour writing jollification!

My writing sessions are intensely focused, fun, and productive.

But is that all really thanks to a superstitious pattern of actions? Francesca Gino and Michael Norton would answer yes. In a way-too short co-authored article in the Scientific American, the researchers explain that ritual work, whether or not they are rational or irrational. And they work even if you don’t believe in the efficacy of rituals.

In the Lab

Gino and Norton conducted experiments where participants were given a task, but half of them first had to carry out a small, superstitious acts or rituals like crossing their fingers or touching a lucky talisman. The half that engaged in the ritual performed better overall on the task. They gave invested more effort, demonstrated enhanced confidence, and did better on future tasks that did not require a ritual. (Even participants who said before the experiment that they did not believe in rituals or superstitions performed better when they executed a ritualistic or superstitious behavior!)

And the results seem to be consistent around the world and across cultures. Hardly a surprise, considering how many rituals we see globally. Rituals seem to decorate the entire tapestry of human history. In the 1940s, anthropologists observed a ritualistic pattern in an indigenous tribal community in the South Pacific.Whenever the fisherman set out to fish in the calm lagoon, they just hopped into the water and fished. But whenever they set out to fish in the shark infested sea, they always performed a ritual to seek protection from the gods.

Whenever uncertainty or risk run high, we humans need a ritual.

Sports psychologists have seen and studied the ritual phenomenon for a long time. Michael Jordan always wore his North Carolina shorts under his Bulls uniform. Boston Red Sox third basemen Wade Boggs wrote the Hebrew word “chai” (living) in the dirt before each at bat. The entire Kansas City Royals team spritzed on some Victoria’s Secret perfume and listened to the same rap song before each game. Between every serve, Maria Sharipova does this seemingly anal five-count foot shuffle-shuffle-shuffle. The list goes on and on.

And did these athletes enjoy a better performance? Well, I’ll let you Wikipedia the results if you don’t already know.

Gray MattersThe real question is why? Why do rituals have this effect on us?

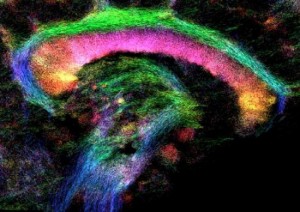

If you fMRI the brain while someone performs a ritual (praying, meditating, or some other ritualized action), what you will see is a deactivation of the parietal lobe, the area most associated with processing and sensory stimulus. Turning off your parietal lobe is like disconnecting from the world around you. Shutting off “reality.”

The next thing you’ll see is the frontal lobes fully activate. These lobes are involved in our ability to focus and concentrate.

Finally, you’ll also see the amygdala go into hyperdrive. This area of the brain is thought to be the center of our primal emotions: fear, joy, panic, relaxation. A hyperactive amygdala is not necessarily a condition you want to provoke in the body. See Norman Doidge’s new book, The Brain’s Way of Healing, for some pretty disturbing disorders (rife with panic attacks) linked to an inflamed amygdala. But in the case of rituals, the amygdala’s inflammation produces more joyful and relaxed emotions, leaving fear and panic in the backseat.

And with your brain operating in this manner, what you get is that intensely revved up flow state that Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi identified in the brains of the world top athletes, artists, and business leaders. You know this state of mind if you’ve ever gotten so wrapped up in a task that the external world just peeled away and it was impossible to tell if a minute spanned an hour or an hour spanned a millisecond.

Ritual or Habitual?But herein lies the rub: to get your brain into this altered state, you have to perform a ritual, and not just some rutted habit. On the surface, rituals and habits seem almost identical. They are both sequenced or patterned behaviors that recur in the same way. The difference between rituals and habits boils down to intent. You do a ritual in order to achieve a particular outcome: hit the ball out of the park, sink fifty three-pointers, ace every serve, win the World Series or write one helluva good novel!

If we look back on my morning ablutions, my trek around the house switching on appliances and making the coffee is a habit. I do it the same way because it turned out to be the most efficient system, not because I think it will make me a better writer. Breaking off the chocolate, whispering my little prayer, and savoring the chocolate? That is definitely a ritual because I certainly duplicate that pattern of actions with a desired outcome in mind. Besides being the food of gods, chocolate has also been shown to relax the brain and promote creativity. So it’s basically my vitamin-W (vitamin Write).

Yes, I know it’s Dumbo’s feather. I don’t technically need it. I already have the ability to go sit down for two hours and knock out a couple thousand words. But diving into a writing project is not that different from plunging into shark infested waters. And if doing a little ritual is going to help me maneuver with poise among a bloodthirsty flock of sharp-toothed torpedoes, well then…mekalekahi-mekahini-ho!

The best part about this research on rituals is that you can truly tailor-make your own ritual. So long as you do it with a desired outcome in mind, it does not matter what actions go into your ritual. Cross your heart. Light a candle. Whisper a chant. Turn in circles three times and bark like a dog. Anything goes!

So what is your ritual (or should I say writual)? What do you do when the sharks begin to circle?

For further reading:

How Enlightenment Changes Your Brain: The New Science of Transformation by Andrew Newberg

The Brain’s Way of Healing: Remarkable Discoveries and Recoveries from the Frontiers of Neuroplasticity by Norman Doidge

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Comments