In this delightful, subversive novel, Voigt gives young readers everything they usually aren’t supposed to get: strangers, dangers, and unanswered questions.

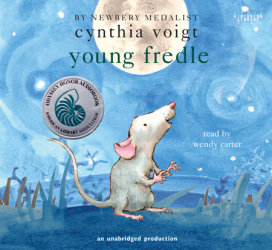

Voigt, Cynthia. Young Fredle. Illus. Louise Yates. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011. Print.

Genre: middle grade

Summary: Separated from his home and family in the walls of the house, Fredle the young mouse must make his own way in the outside world. Deadly barn cats, owls, scamming field mice, snakes, and raccoons are just some of the hazards he encounters. When Fredle finally does find the way back home, he is not sure he can give up stargazing, flowers, and all his new friends.

Critique: One night, while scouring the dark kitchen floors for food, Fredle finds an unknown object. Flat and round and with a ridged edge, the thing tasted of metal. It was not food, but he still wanted to know what it was. His family and all the other mice warn him not to wonder. Wondering is how good mice get “went.”

Readers remain actively engaged throughout this novel because Voigt is a master of crafting inference moments. Fredle may not know what a coin is, but we do and we can infer it from the description provided. Fredle also does not know about stars, flowers, rain, chickens, owls, raccoons, snakes, grass, dirt, and so many other things. For each encounter with a new thing or creature, Voigt takes her time relaying all the clues readers need to solve the riddle.

As a result, young readers accumulate a sense of mastery, feeling clever and knowledgeable. By providing these inference moments, the author cunningly mirrors and echoes Fredle’s feelings and experiences as he learns more and more about the world. He too feels increasingly knowledgeable, clever, and adroit.

Fredle also encounters strangers: Bardo and Neldo, the field mice; Angus and Sadie, the dogs; Tarnu, Ellnu, and all the cellar mice. He learns skepticism and trust. Not everyone is as altruistic as they seem, and not everyone is as dangerous as we might like to assume.

Like a good teacher, Voigt’s narration is very patient. When a trap snaps, all the mice flee. Readers wait a long time before discovering which mouse just got “went.” When a band of raccoons thieves from the trash the ice cream carton with young Fredle inside, readers again wait a good while before Fredle is discovered. Will they crunch him as a snack, will he escape, or will they induct him into their gang? The answer unfolds gradually.

Other times, answers do not unfold at all because Voigt is unafraid to ask potentially unanswerable questions. For instance, should we honor tradition and remain close with our family and community, or should we change and adapt with life’s waxing, waning rhythms even though those changes lead us far away from the home and family we love? What should we love more: family or self?

Failing to supply a ready answer is simultaneously a great taboo and mighty treasure. Too often, we adults rush in with answers for all the queries young people have. We tend to believe danger lurks in the dark, blank spaces. But a dark, blank space can also be home to trillions of stars. A gap can be gain, such as when space makes way for growth.

Kommentare